Large-scale fire experiments for humanitarian shelters

Place

Focus

Status

Outputs

What it is

Watch our educational films below!

Overview

Understanding how fires spread in informal and humanitarian settlements is critical to improving safety and saving lives. But little scientific data existed on how shelters built of different materials, such as mud, thatch, bamboo, timber, sheet metal, and tarpaulin, actually burn and contribute to fire spread.

This project established a new benchmark for analysing fire hazards posed by diverse shelter materials, bridging a major research gap. While fire science has long studied single-room fires with non-combustible walls, and more recent work has focused on sheet-metal dwellings found in South Africa, neither reflects the full range of materials used globally.

By testing shelters built from these varied materials, Kindling’s large-scale fire experiments make it possible to compare fire behaviour across diverse contexts enabling development of evidence-based guidance that moves beyond a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

“It’s important because it covers materials that wouldn’t traditionally be researched as they are immediately discounted from any notion of being used in any formal fire engineering”

- Sam Stevens

Fire Safety Engineer

The challenge

In humanitarian and informal settlements, small fires often escalate into large conflagrations that destroy hundreds or even thousands of homes.

In 2017, more than 2,000 dwellings were lost in the Imizamo Yethu informal settlement in South Africa. Four years later, a fire in the Rohingya refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, damaged over 10,000 shelters and displaced more than 45,000 people.

Why do these large fires happen?

In many informal and humanitarian settlements, shelters are built from highly combustible materials and packed tightly together. When a small fire starts, flames, radiant heat, and firebrands can easily spread fire from one shelter

to the next. These conditions create the potential for rapid, settlement-scale fire spread, turning a single ignition into a disaster affecting hundreds or even thousands of people.

Despite the scale of these events, there remains a major gap in understanding how fires develop and spread between shelters of different materials. Much of today’s fire science on compartment fires, external flaming, and firebrand dynamics was developed for formal buildings. Its relevance to informal or humanitarian settlements, where structures and layouts differ drastically, is uncertain.

When shelters burn, they may spread fire through direct flame impingement, radiation, or the production of firebrands capable of igniting neighbouring structures. The influence of each mechanism depends on the shelter’s materials, distance between shelters and on environmental factors such as wind.

Existing guidance for humanitarian settings offers short sets of prescriptive rules that are disconnected from the principles of fire science and rarely achievable in real settlements. A central challenge in producing more flexible, evidence-based fire safety guidance is the lack of contextualised experimental data.

Guiding questions

The way fires spread between shelters depends on many interacting factors. At its simplest, there must be something on fire (hazard), something for it to spread to (vulnerability), and conditions that allow the two to interact (exposure).

Together, these elements determine whether a small fire stays contained or grows into a settlement-scale fire.

The materials shelters are built from play a defining role. Some ignite quickly and burn intensely; others resist ignition but radiate enough heat to spread fire to their neighbours.

- How do shelters of different materials burn?

- What hazards do they present?

- How quickly do those materials ignite?

Global relevance

Kindling conducted large-scale fire experiments to study how whole shelters behave when they burn, and smaller laboratory tests to understand how different materials ignite.

Because it was impossible to test every type of shelter in use around the world, we built a database of over 450 shelters from 90 countries to identify the most common wall and roof materials so we could design experiments that reflect diverse real-world conditions.

We conducted 20 full-scale shelter burns, each representing a distinct combination of wall and roof materials. These included non-combustible materials such as sheet metal, cement block, and mud as well as combustible materials such as timber, split bamboo, woven bamboo, plastic tarpaulin, and thatch. Different material combinations reflected the diversity of global shelter construction and allowed direct comparison of how different wall and roof materials influence fire growth and spread.

Demonstration or experiment?

The purpose of an experiment is not only to observe how fire behaves but to measure and quantify it. To do this, we use an array of specialized instruments that capture the physical properties of fire in real time.

This level of preparation is what transforms a simple burn demonstration into a scientific experiment—producing quantitative evidence about how shelters ignite, burn, and spread fire to their surroundings.

Experimental Design

We installed more than three miles of cabling to connect sensors, scales, cameras, and data loggers, each carefully routed, tested, and secured to withstand extreme heat and ensure reliable data once the burns began.

We used a range of instruments to capture key physical properties of the fire:

- A 6-ton platform scale measured the shelter’s mass loss during burning, allowing us to calculate the fire’s heat release rate (the amount of energy produced over time),

- Thermocouples recorded temperatures inside the shelter to track how heat developed and spread,

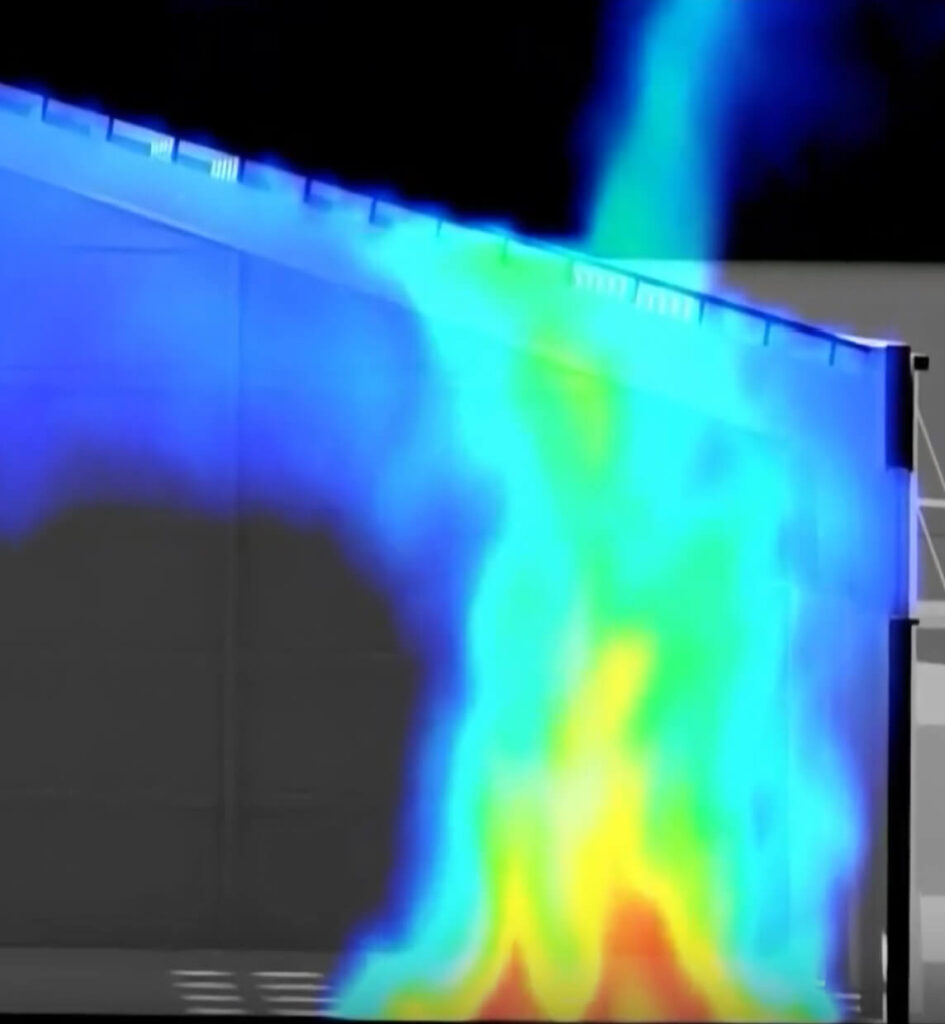

- Heat flux sensors around the exterior measured how much energy radiated outward, mapping how heat spread into surrounding areas,

- Anemometers and a weathervane recorded wind speed and direction, and

- Cameras captured the size, location, and behavior of flames throughout each burn.

Together, these measurements create a detailed picture of how a burning shelter can contribute to a rapidly spreading fire within a settlement.

Fire science in action

For our fire experiments, we installed more than three miles of cabling to connect sensors, scales, cameras, and data loggers—each carefully routed, tested, and secured to withstand extreme heat and ensure reliable data once the burns began.

We used a range of instruments to capture key physical properties of the fire:

- A 6-ton platform scale measured the shelter’s mass loss during burning, allowing us to calculate the fire’s heat release rate—the amount of energy produced over time.

- Thermocouples recorded temperature inside the shelter to track how heat developed and spread.

- Heat flux sensors around the exterior measured how much energy radiated outward, mapping how heat spread into surrounding areas.

- Anemometers and a weathervane recorded wind speed and direction.

- Cameras captured the size, location, and behavior of flames throughout each burn.

Together, these measurements create a detailed picture of how a burning shelter can contribute to a rapidly spreading fire within a settlement.

Early insights

While detailed analysis of the fire experiments will be released in early 2026 along with the full data set and guidance, we can share initial findings now.

The broad spectrum of fire behaviour observed and measured strongly suggests that different fire spread mechanisms will dominate in shelters of different materiality:

- Shelters built with non-combustible materials tend to exhibit conventional compartment fire dynamics with the potential for fire spread between shelters dominated by external flames from door and window openings,

- Combustible walls add the hazard of high heat fluxes and the potential for flame impingement around the entire shelter perimeter as the walls burn, impingement around the entire shelter perimeter as the walls burn,

- Combustible roofs introduce the potential for a flame plume to establish on the roof– particularly if that roof is thatch– and when the roof burns through, allow hot gases to be vented vertically through the roof, reducing or eliminating external venting flames from doors and windows.

Experiments in high winds support existing evidence of the significant influence of wind on settlement fire spread, with flames from the leeward side of burning shelters extending to lengths of 3-4m from the shelter.

This program provides a benchmark for analysing the fire hazards presented by shelters of different materiality where previously little to no data existed, an important step towards engineering safer communities.

Watch our educational films

We’re proud to share five educational films that introduce the program and present our initial findings — insights you can begin applying in your own work today:

Comprehensive analysis of data from this experimental program is still underway, with detailed reports and practical guidance to be released in early 2026.

Sponsor

Collaborators

We are grateful for our collaboration with three leading academic institutions on the design, implementation, and analysis of this fire experimental program.